ARTIST

My name is Lauren Boyle. I’m here with you today, I think, because of my work with my – the collective that I started in 2010 with a big group of friends.

I’m part of a collective called DIS. and DIS is –_right now, what we’re working on, is like a streaming platform for education entertainment which we worked with artists and academics and scholars and just like great thinkers to kind of translate this really big broad ideas – complex ideas into something that can be watched, you know, in like 5, 10, 15 minutes without simplifying them, without kind of like dimming it down and actually maybe even adding another layer of complexity through like visuals. So, you know, we look for ideas, that don’t have clear answers, but maybe propose possible like solutions or an open end or imagine something else. We started out as a magazine back into 2010, which I don’t think there can be anything more collaborative or generative than a magazine as a format. And since then we’ve just basically moved from kind of like rethinking formats, like one to the next, you know, over the last decade – it’s a decade now.

DIS is a prefix. So, in English it just kind of takes everything into the opposite of whatever it is. So, it’s like taste or distaste. You know, distaste is like oppositional, it’s antagonistic, it’s like whatever. So, when we were looking for names for the magazine, we had one idea was, that, you know, we would be issue-based and every issue should be a different DIS word, you know, in a sense. In the end we rounded up just having a kind of like publishing like in a kind of much more like fluid rolling way, you know, we didn’t publish issues super regularly, but we had different kind of like top(ics), it’s like distaste, dystopia, disco, all of that kind of covered culture in a really brought way. But, it was meant to be pretty negative or at least we thought, that it’s going to be kind of like very negative and antagonistic magazine that would flip everything on a tab, like upside down in a way. Because everything at that moment was very like, you know,) positive and consumeristic and like – there wasn’t really like a good critique happening – in our minds – so we thought that we could kind of like interject something new, by kind of taking an oppositional approach to it. So, that’s where the word DIS comes from.

I think it was in 2009, that we started. Simon and David, who’s a couple, they are still part of DIS, they send an e-mail out to like a group of friends. It was rather ambiguous, it was kind of vague and they just said: “Let’s do something, should we do something?” Because everyone was out of work and was kind of – it was like, just after the financial collapse, the housing market and all of that and kind of like peering into like the great recession. So, we just had a lot of time on our hands, more time, you know – everyone was on unemployment insurance, it felt like – whatever, you know. And we just started having meetings at my house. Just like a big group of friends really, you know, that just got smaller and smaller over time. Based on who had the most interest in staying active and involved and things like that. So, that’s, how it began. And we kind of knew at the outside, that it was going to be like a digital, like an online magazine. We weren’t going to bother with printing which was expensive and also analog. And that was really created by just the content that we were interested in: like the people we wanted to talk to and the conversations we wanted to have, were all basically about the internet and technology and how it’s kind of shifting our minds and behaviors in a way. So, it would have felt really weird to print something like that, you know. Like, you can’t print a GIF and you know, whatever. And at the moment, like all the other magazines, that were considered like, you know cultural icons and beacons – it was still like wise and purple, you know. Like self-service – I don’t know – you know it’s all these kind of magazines that were doing their best just to ignore the internet. And so, I think when we launched, it was like kind of immediately shocking to people.

DIS Magazine probably was like – I mean, it couldn’t have happened without Facebook. I mean, the engagement, that we were – the audience we were able to find through Facebook naturally, very organically, just through friends of friends of friends, you know, this kind of like node in a network, happened very quickly and it was kind of, you know, could never be recreated. You know, it was just the right time and the right place. But, by the time, you know, 2014, 2015/16 like they have been changing the rules and kind of pushing the goalpost in terms of like, how you could reach people. For a really long time you had to actually – (interruption) So, basically like by the time, we did the Berlin Biennial and came back to the States. We had still been publishing on DIS Magazine throughout that whole like period. When we came back, everything had changed, you know. I mean, we were confronted with a new president, like the rise of nationalism, all these things were kind of like coming to our head, but we also realized, that there was – there was just no hope in staying an independent magazine any longer. I mean, there was no means to connect to people, the way that there once was. If you even think about, how many blogs existed in that period, in like 2010, 2014, how many small like, you know whatever. Just like it was just so, there was a lot of media and options, but they had kind of gotten consolidated and consolidated and definitely this magazine was not going to make it in that way anymore. So, we had to think about like a completely new distribution model. At the same time, we had to think about how people were consuming information and how that was really changing a lot. Like people no longer wanted to read, you know like 5000-word essays, like I don’t know, if they ever did, but they didn’t do it anymore. And there was this huge movement towards podcasts and audiobooks and video, and we thought, that we had an opportunity basically to change original programing, you know. To kind of infuse it with something else and like confront some like bigger, broader issues, that we thought, were really critical at the moment. So, we took the time to think about like other ways of like producing content and distributing content. And what we kind of came up with was, that we would be doing, you know, exclusively video, video – accompanied by text, sure, but exclusively video focus on people who had like a real wealth of information or research in their body of work, but that maybe, you know, got lost in the wall text or a catalogue or got lost, you know, in one of those like myriad of like books that come out every year and take the most interesting ones and people turn them into videos, that kind of basically be like a sort of, you know, it’s like a gateway to their studies or something for people.

So, we wanted to think about how could we find our audience without going through the pain of like A) paying tons of money, you know to promote our content on Facebook or Instagram or Twitter, wherever and not have to make like headlines, that are just like really sensational and like news like for 24 hours 7, you know, to try to compete in that space and become like another Vice or something. We wanted to think like much more long term, with like a higher, wider perspective. And the only way, that we could see, doing that, was actually just directly working with like public institutions, like particularly – well, public or private universities, public libraries and museums, that kind of provide like every student – you know, that’s the goal, that every student has access to DIS.art through their schools. It just becomes a kind of eager of it’s like – it’s there, you know. So, know we’re just in a process of like signing up schools, so that everyone has access to DIS and we don’t have to, you know, change the content in order to fit the medium of social media and the normal, like road of content production.

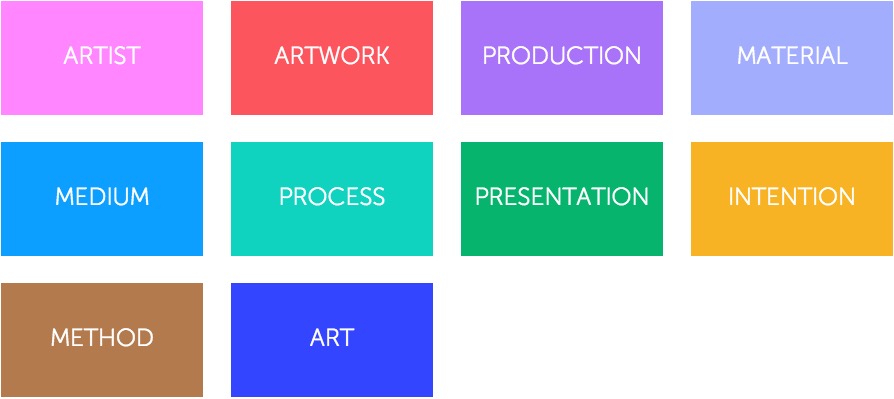

I’m not that invested in the nomenclature of like, who is an artist, who is not an artist. I mean, there is probably a couple of reasons for that. One, like who gets afforded the opportunity to do that. You know, like who really gets a chance, to have free time, that they can explore, reflect on the world and then produce something? I mean, it’s such a privilege thing, you know, that I just don’t – I mean, I do identify with it to a degree, but I just don’t try to put it on like a pedestal, as like the greatest thing you can do. There is like labor activism, mothers and caretakers, you know, who are doing like really important work and don’t get any credit for it ever, you know. So, there is that – but there also – I just, it‘s sort of like – is it interesting or not interesting? – you know. That‘s like what is more important than whether something is like art or someone is an artist or not. When I went to college, I thought, I was going to study fashion. I was always really into art, but I also thought, like fashion would be like a good place for me. And I went to school after like one week of classes, I was just like, yes no, like this is an – it was the wrong environment for me. You know, it was the conversations and the people, that I kind of – I was like, I’m not going to study four years here. I’m going to – and I immediately switched over to like the sculpture and like the art department. And I think that‘s like kind of how I‘ve always kind of like just been like – as almost – like you just kind of go wherever the most interesting conversations are and that‘s just where – you know, that changes too in a way. Yes. And I guess, because I don‘t work in this, like even I probably have hang-ups about what is an artist you know. Like, working in a studio, making painting, producing things, having art shows. We do have art shows, we do work in studios sometimes, you know, like producing videos or this or that. So, we do a lot of those things, but in the end we’re also, like we really are facilitators and organizers in a much broader community, in a sense. Yes, that seems for me to take precedence, personally.